Act II

TWENTY-FIVE DAYS after he buried his father and 15 before the 2006 U.S. Open, Tiger went back to visit the Navy SEALs, this time to a hidden mountain training facility east of San Diego. The place is known as La Posta, and it's located on a barren stretch of winding road near the Mexican border. Everything is a shade of muted tan and green, like Afghanistan, with boulders the size of cars along the highway.

This time, Tiger came to do more than watch.

He tried the SR-25 sniper rifle and the SEALs' pistol of choice, the Sig Sauer P226. One of the instructors was Petty Officer 1st Class John Brown, whose father also served as a Green Beret in Vietnam. Brown pulled Tiger aside. The sun was shining, a nice day, and the two men talked, standing on the northeast corner of a shooting facility.

"Why are you here?" Brown remembers asking.

"My dad," Tiger said, explaining that Earl had told him he'd either end up being a golfer or a special operations soldier. "My dad told me I had two paths to choose from."

Brown says Tiger seemed to genuinely want to know about their way of life. Tiger asked questions about Brown's family and they figured out that Brown's wife and Tiger shared the same birthday. Tiger told him not to ever try to match Michael Jordan drink for drink. They talked about Earl, and Brown felt like Tiger wanted "safe harbor" from his grief, a way to purge some of it even, to prove something to himself, or maybe prove something to the spirit of Earl, whose special ops career never approached the daring of a SEAL team.

"I definitely think he was searching for something," Brown says. "Most people have to live with their regrets. But he got to experience a taste of what might have been."

The instructors gave Tiger camo pants and a brown T-shirt. He carried an M4 assault rifle and strapped a pistol to his right leg. On a strip of white tape above his right hip pocket, someone wrote "TIGER." SEAL Ben Marshall (his name has been changed for this story because he remains on active duty) took Tiger to the Kill House, the high-stress combat simulator where SEALs practice clearing rooms and rescuing hostages. Marshall is a veteran of many combat deployments and was with Tiger making sure he didn't get too hurt. The instructors ran the golfer through the house over and over, lighting him up with Simunition, high-powered paint rounds that leave big, painful bruises. "It was so much fun to hit him," Marshall says. "He looked like a deer in the headlights. I was spraying him up like it was nothing."

The instructors set up targets, some of terrorists holding weapons and others of innocent civilians. Under fire and stress, Tiger needed to decide who should die and who should live. During one trip through the Kill House, the guys switched out a target of someone with a gun for one of a photographer, and when Tiger came through the door, he killed the person with the camera, according to two witnesses. The SEALs asked why he'd shot a civilian.

First Tiger apologized for his mistake.

Then he made a joke about hating photographers.

Eventually, Woods learned how to clear a room, working corners and figuring out lanes of fire, doing something only a handful of civilians are ever allowed to do: run through mock gun battles with actual Navy SEALs. "He can move through the house," says Ed Hiner, a retired SEAL who helped oversee training during the time and wrote a book called First, Fast, Fearless. "He's not freaking out. You escalate it. You start shooting and then you start blowing s--- up. A lot of people freak out. It's too loud, it's too crazy. He did well."

At one point, Marshall put him through a combat stress shooting course, making him carry a 30-pound ammunition box, do overhead presses with it, do pushups and run up a hill, with shooting mixed in. Tiger struggled with slowing his heart rate down enough to hit the targets, but he attacked the course.

"He went all out," Marshall said. "He just f---ing went all out."

Marshall got his golf clubs at one point and asked Tiger to sign his TaylorMade bag. Tiger refused, sheepishly, saying he couldn't sign a competing brand. So Marshall challenged him to a driving contest for the signature. Both Marshall and Brown confirmed what happened next: Tiger grinned and agreed. Some other guys gathered around a raised area overlooking the shooting range. Marshall went first and hit a solid drive, around 260 or 270 yards. Tiger looked at him and teed up a ball, gripping the TaylorMade driver.

Then he got down on his knees.

He swung the club like a baseball bat and crushed one out past Marshall's drive. Tiger started laughing, and then all the SEALs started laughing, and eventually Marshall was laughing too.

"Well, I can just shoot you now and you can die," Marshall joked, "or you can run and die tired."

Tiger juggled many women, including Rachel Uchitel (left), Cori Rist (center) and Jaimee Grubbs (right), looking for something he couldn't find. Getty Images

THE MILITARY MEN and their bravado sent Tiger back in time to the Navy golf course with Earl and those salty retired soldiers and sailors. He missed his dad, of course, but he also missed the idea of Earl, which was as important as the man himself. Sometimes his dad traveled to tournaments and never visited the course, staying put at a hotel or rented house in case Tiger needed him. They could talk about anything, from the big questions of life, like Tiger's completely earnest belief in ghosts, to simple things a man should know, like how to order spacers of water between beers to keep from getting so drunk. (That last bit came about after a bad night at a Stanford fraternity party.) Without Earl, Tiger felt adrift and lonely. He threw himself back into his circus of a life, moving from place to place. And in the months after the funeral, the extramarital affairs either began or intensified. That summer of 2006, he met at least two of the mistresses who'd eventually hit the tabloids.

To be clear, he'd always talked a good game about women, long before he married Elin Nordegren in 2004. In 1999, in the quiet Oregon woods near the Deschutes River with Mark O'Meara and one of the best steelhead guides in the world, Tiger held court about the perks of being a professional athlete. "I'm walking down the trail with him and he's bragging about his sexual conquests," says guide Amy Hazel. "And this is when everybody thought he was the golden boy."

He told just filthy stories that Hazel wouldn't repeat, but even with the boasts and dirty jokes, she saw him as more of a big kid than a playboy. "Nerdy and socially awkward" are her words, and he seemed happiest standing in the river riffing lines from the Dalai Lama scene inCaddyshack.

The sexual bravado hid his awkwardness around women. One night he went to a club in New York with Derek Jeter and Michael Jordan. Jeter and Jordan circulated, talking with ease to one beautiful woman after another. (Both declined to comment about the episode.) At one point, Tiger walked up to them and asked the question that lives in the heart of every junior high boy and nearly every grown man too.

"What do you do to talk to girls?"

Jeter and Jordan looked at each other, then back at Tiger, sort of stunned.

Go tell 'em you're Tiger Woods, they said.

If Tiger was looking for something, it was seemingly lots of different things, finding pieces in a rotating cast of people. He and Rachel Uchitel bonded over their mutual grief. His fresh wounds from losing Earl helped him understand her scars from her father's cocaine overdose when she was 15, and her fiancé's death in the World Trade Center on Sept. 11. The broken parts of themselves fit together, according to her best friend, Tim Bitici. Sometimes Rachel stayed with Tiger for days, Bitici says. Nobody ever seemed to ask Tiger where he was or what he was doing. Bitici went with Rachel down to Orlando to visit Tiger, who put them up in a condo near his house. When he came over, he walked in and closed all the blinds. Then he sat between Tim and Rachel on the couch and they all watched Chelsea Lately.

"This makes me so happy," Tiger said, according to Bitici.

Many of these relationships had that odd domestic quality, which got mostly ignored in favor of the tabloid splash of threesomes. Tiger once met Jaimee Grubbs in a hotel room, she told a magazine, and instead of getting right down to business, they watched a Tom Hanks movie and cuddled. Cori Rist remembered breakfast in bed. "It was very normal and traditional in a sense," she says. "He was trying to push that whole image and lifestyle away just to have something real. Even if it's just for a night."

Many times, he couldn't sleep.

Insomnia plagued him, and he'd end up awake for days. Bitici says that Tiger asked Rachel to meet him when he'd gone too long without sleep. Only after she arrived could he nod off. Bitici thinks Tiger just wanted a witness to his life. Not the famous life people saw from outside but the real one, where he kept the few things that belonged only to him. This wasn't a series of one-night stands but something more complex and strange. He called women constantly, war-dialing until they picked up, sometimes just to narrate simple everyday activities. When they didn't answer, he called their friends. Sometimes he talked to them about Earl and his childhood.

We never see the past coming up behind because shaping the future takes so much effort. That's one of those lessons everyone must learn for themselves, including Tiger Woods. He juggled a harem of women at once, looking for something he couldn't find, while he made more and more time for his obsession with the military, and he either ignored or did not notice the repeating patterns from Earl's life. "Mirror, mirror on the wall, we grow up like our daddy after all," says Paul Fregia, first director of the Tiger Woods Foundation. "In some respects, he became what he loathed about his father."

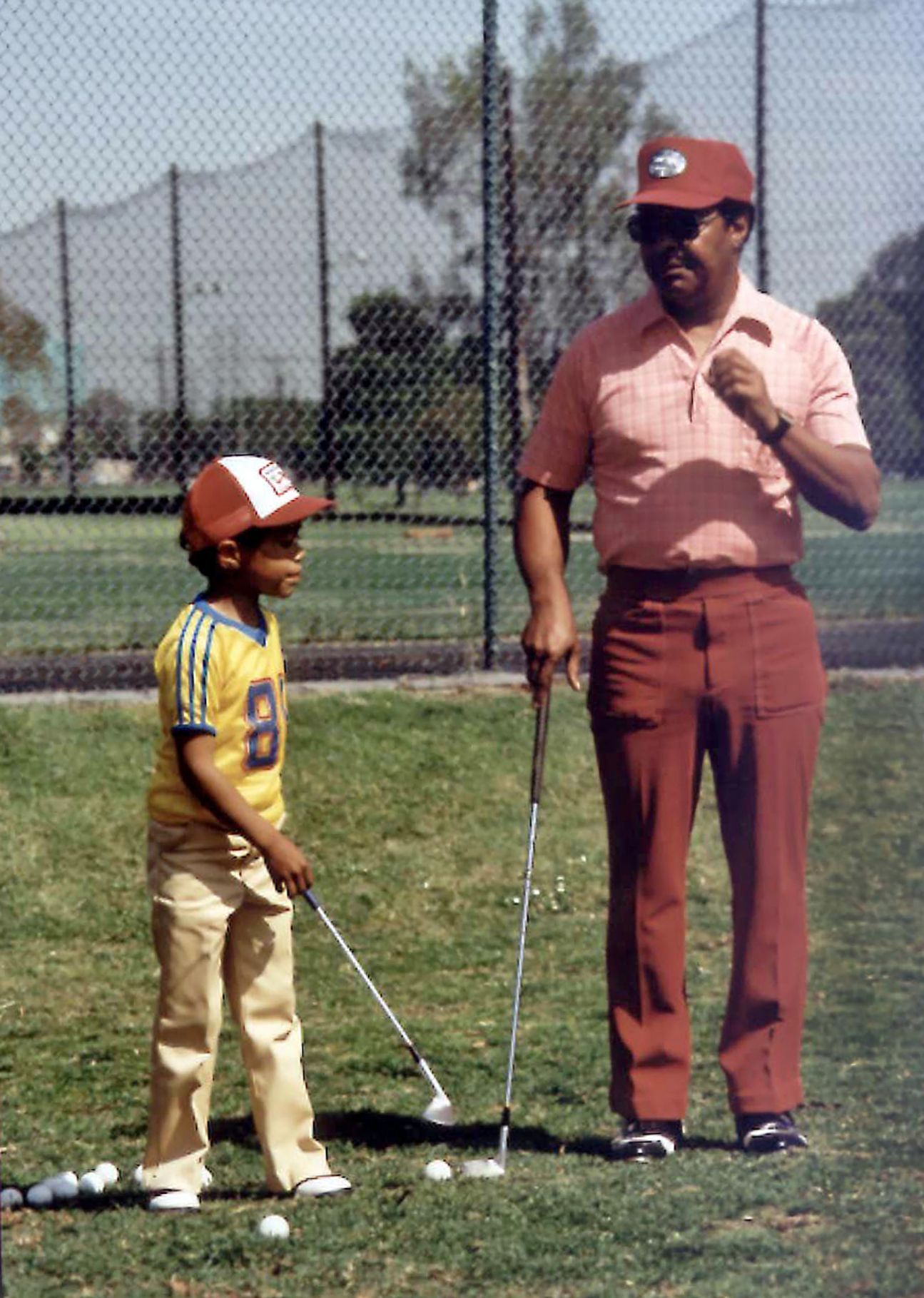

Tiger told numerous Navy SEALs -- whose facial features ESPN is protecting because some remain on active duty -- that he wanted to be a SEAL when he was young and follow in his father's special ops lifestyle. Courtesy Wright Thompson

“I definitely think he was searching for something. Most people have to live with their regrets. But he got to experience a taste of what might have been.”

- PETTY OFFICER 1ST CLASS JOHN BROWN ON TIGER TRAINING WITH SEALS

Some SEALs complained that Tiger was only doing the fun stuff, shooting guns and jumping out of airplanes, but never the brutal, awful parts of being a SEAL. U.S. Navy photo by Chief Journalist Deborah Carson

THE MILITARY TRIPS continued through 2006 into 2007, kept almost completely a secret. At home, Tiger read books on SEALs and watched the documentary about BUD/S Class 234 over and over. He played Call of Duty for hours straight, so into the fantasy that his friends joked that after Tiger got shot in the game they might find him dead on the couch. When he could, he spent time with real-life operators. Tiger shot guns, learned combat tactics and did free-fall skydiving with active-duty SEALs. During one trip to La Posta, he remembered things they'd told him about their families, asking about wives, things he didn't do in the golf world; Mark O'Meara said Tiger never asks about his kids.

"If Tiger was around other professional athletes, storytelling would always have a nature of one-upmanship," a friend says. "If Tiger was around some sort of active or retired military personnel, he was all ears. He was genuinely interested in what they had to say. Any time he told a military-related story that he had heard or talked about a tactic he had learned, he had a smile on his face. I can't say that about anything else."

One evening, Brown and two other guys put Tiger in the back seat of a king-cab pickup truck and drove him an hour and a half out into the desert to a training base named Niland, where a SEAL team was doing its final predeployment workup, staging a raid on a mock Afghan village that had been built down in a valley. They stood on a hill looking into the darkness. The SEAL platoon charged toward the position. Flares popped off, trailing into the darkness, and the valley rocked with the deep boom of artillery simulation and the chatter of small-arms fire. In the glow, Tiger looked transfixed. "It was f---ing awesome," Brown says, laughing. "I don't know if we just got a glimpse of him in a different light, but he just seemed incredibly humble, grateful."

"He can literally think himself through the skydives," says Billy Helmers, a SEAL who jumped with Tiger, shown here skydiving in San Diego. Splash News

His golfing team, particularly swing coach Hank Haney, understood the risk, sending a long email scolding Tiger for putting his career at risk: You need to get that whole SEALs thing out of your system. Haney does a lot of benefit work, including some for the special operations community, so stories would later trickle back to him about injuries suffered during training. Caddie Steve Williams thought the 2006 U.S. Open, where Tiger missed his first major cut as a pro, was the first time he'd ever seen Woods not mentally prepared. Tiger talked openly about the grief and loss he felt when he practiced, since that activity was so closely wound together with his memories of his dad.

The moments with the military added some joy to what he has repeatedly called the worst year of his life, and he chose to spend Dec. 30, 2006 -- his 31st birthday -- in San Diego skydiving with SEALs. This was his second skydiving trip; a month earlier, in the middle of a seven-tournament win streak, he'd gotten his free-fall USPA A-license, now able to jump without a tandem. Across the country, in Florida, his reps put a news release on his website, revealing for the first time that Elin was pregnant. Tiger Woods was going to be a father.

Elin came with him to San Diego on his birthday, and they rode south and east of the city, near a land preserve a few miles from Mexico, halfway between Chula Vista and Tecate. The road curved at banked angles, and up ahead a small airport came into view. Nichol's Field is a collection of maybe two dozen buildings. To the east of the property, a cluster of metal huts sat behind red stop signs: warning, restricted area. This was Tactical Air Operations, one of the places where the SEALs practice jumps. The main building felt like an inner sanctum: a SEAL flag on the wall and parachute riggings hung from the ceiling. They wore blue-and-white jumpsuits, Tiger and the three or four SEALs. He learned advanced air maneuvers. After each jump, the guys would tell Tiger what to do differently and he'd go off by himself for a bit to visualize the next jump and then go back up in the plane and dive into the air, doing everything they'd said. "The dude's amazing," says Billy Helmers, a SEAL who jumped with him that day. "He can literally think himself through the skydives."

The SEALs put a birthday cake on a table in one of the Tac Air buildings. It had a skydiver decorated on it in icing and read "Happy Birthday, Tiger!" The team guys and their families gathered around and sang "Happy Birthday," and then Tiger leaned in and blew out his candles. Everyone took pictures, and in them Tiger is smiling, and it's not the grin that people know from commercials and news conferences. He looks unwatched and calm.

WHILE HE MADE friends with some of the SEALs, many of their fellow operators didn't know why Tiger wanted to play soldier. It rubbed them the wrong way. Guys saw him doing the fun stuff, shooting guns and jumping out of airplanes, but never the brutal, awful parts of being a SEAL, soaking for hours in hypothermic waters, so covered in sand and grit that the skin simply grinds away. One year during hell week, a BUD/S candidate collapsed, his body temperature below 90 degrees; the man, a former wrestler, would rather have frozen to death than quit.

Was Tiger willing to do that?

"Tiger Woods never got wet and sandy," says former SEAL and current Montana congressman Ryan Zinke, who ran the training facility during the years Tiger came around. The BUD/S instructors didn't like the way Tiger talked about how he'd have been a SEAL if he didn't choose golf. "I just reached out to the guys I know who jumped with him and interacted with him," says a retired SEAL. "Not a single one wants to have any involvement, or have their name mentioned in the press anywhere near his. His interactions with the guys were not always the most stellar, and most were very underwhelmed with him as a man."

Then there's the story of the lunch, which spread throughout the Naval Special Warfare community. Guys still tell it, almost a decade later. Tiger and a group of five or six went to a diner in La Posta. The waitress brought the check and the table went silent, according to two people there that day. Nobody said anything and neither did Tiger, and the other guys sort of looked at one another.

Finally one of the SEALs said, "Separate checks, please."

The waitress walked away.

"We are all baffled," says one SEAL, a veteran of numerous combat deployments. "We are sitting there with Tiger f---ing Woods, who probably makes more than all of us combined in a day. He's shooting our ammo, taking our time. He's a weird f---ing guy. That's weird s---. Something's wrong with you."

“It was very normal and traditional in a sense. He was trying to push that whole image and lifestyle away just to have something real. Even if it's just for a night.”

- CORI RIST, ONE OF TIGER'S MISTRESSES

THEY'RE NOT WRONG, not exactly, but the SEALs are also viewing Tiger through their own pre-existing idea of how a superstar should act, so his behavior processes as arrogant and selfish. That reaction has colored Tiger's relationships his entire life: People who meet him for 30 seconds love him, and people who spend several hours with him think he's aloof and weird, while people who hang around long enough to know him end up both loving him and being oddly protective. His truest self is shy, awkward and basically well-intentioned, as unsuited for life in public as he is suited for hitting a ball.

"Frankly, the real Tiger Woods isn't that marketable," a friend says. "There isn't a lot of money to be made off a guy who just wants to be left alone to read a book. Or left alone to play fetch with his dog. Or left alone to play with his kids. Or left alone to lift weights. Or left alone to play a video game. Do you see a trend? Tiger was a natural introvert, and the financial interest for him to be extroverted really drove a wedge in his personality. Being a celebrity changed him and he struggled with that -- and he struggled with the fact that he struggled with that."

Tiger uses well-rehearsed set pieces as standard icebreakers -- things that get trotted out again and again. Famously, in front of a GQ reporter in 1997, he told a joke that ended on a punch line about a black guy taking off a condom. He told the same joke in 2006 to a SEAL at a Navy shooting range and to a woman at Butter, a New York nightclub. Talk to enough people who've met him and it starts to seem like he's doing an impersonation of what he thinks a superstar athlete is supposed to be. Once he bought a Porsche Carrera GT, similar to the one driven by many celebrities, but one of the first times he got behind the wheel, the powerful car got away from him, spinning off into the grass near his house. He took it back to the dealership.

Tiger has repeatedly called 2006 the worst year of his life. Here, Tiger, Elin and Tida arrive at a reception after a funeral service for Earl in California. Branimir Kvartuc/AP Images

TIGER BOUGHT A pair of combat boots. They were black, made by the tactical outfitter Blackhawk, popular with ex-special ops guys who become contractors and mercenaries. The boots were inevitable, in hindsight. You can't insert something as intense as the SEAL culture into the mind of someone like Tiger Woods and not have him chase it down a deep, dark hole. He started doing the timed 4-mile run in combat boots, required by everyone who wants to graduate from BUD/S. A friend named Corey Carroll, who refused to comment and whose parents lived near Tiger, did the workouts with him. They'd leave from Carroll's parents' home, heading north, out onto the golf course. The rare sighting was almost too strange to process: Tiger Woods in combat boots, wearing Nike workout pants or long combat-style trousers, depending on the weather, pounding out 8 1/2-minute miles, within striking distance of the time needed for BUD/S.

Tiger knew the SEAL physical requirements by heart, easily knocking out the pushups, pullups and situps. When he couldn't sleep, he'd end up at a nearby Gold's Gym at 3 a.m., grinding. One of his favorite workouts was the ladder, or PT pyramid, a popular Navy SEAL exercise: one pullup, two pushups, three situps, then two, four, six, up to 10, 20, 30 and back down again.

Soon, the training at La Posta didn't cut it. He found something more intense with Duane Dieter, a man allowed by the Navy to train SEALs in a specialized form of martial arts that he invented. Dieter is a divisive figure in the special operations world, working out of his own training compound on the Maryland shore. His method is called Close Quarters Defense, or CQD, and some students look at him as an almost spiritual guide, like a modern samurai. Others think he's overrated. For Dieter, few things were more important than ancient warrior principles like light and dark energy.

Tiger got introduced by the Navy and learned CQD in Coronado. Hooked, he wanted to go further and ended up making trips to Dieter's compound in Maryland. He'd fly in and either stay at the facility or at the nearby fancy resort, Inn at Perry Cabin by Belmond, according to a source who saw Tiger with Dieter. He'd park outside a nearby Target, sending someone else inside for cheap throwaway clothes that they could ruin with the Simunition. The practice rounds left huge bruises. He did all sorts of weapons training and fighting there, including this drill invented by Dieter: He would stand in a room, hands by his side, wearing a helmet with a protective face shield. A hood would be lowered over the helmet and loud white noise would play. It sounded like an approaching train, the speakers turning on and off at random intervals, lasting 30 seconds, or maybe just five. Then the hood would fly up and there would be a scenario. Maybe two people were talking. Or maybe one was a hostile and the other a hostage. If the people posed no threat, the correct response was to check corners and not draw your weapon. Then the hood would go back down, and there'd be more music, and when it came up, the scenario had changed. Sometimes a guy threw punches, to the body and head, and Tiger would need to free himself and draw his weapon. At first, the instructors went easy, not hitting him as hard as they'd hit a SEAL. Tiger put a stop to that and soon they jumped him as aggressively as everyone else. When the drill finally ended, the room smelled like gunpowder.

An idea began to take hold, a dream, really, one that could destroy the disconnect Tiger felt in his life, completely killing off the character he played in public. Maybe he could just disappear into the shadow world of special operations. He mentioned his plans to people around him, one by one. He pulled over a car at a tournament once and told Steve Williams he wanted to join the Navy. He told Haney he thought it would be cool to go through training. Once, Carroll had to talk him down via text message, according to someone present for the exchange, because Tiger wanted to quit golf and join the Navy. There's only one reason to run 4 miles in pants and combat boots. This wasn't some proto-training to develop a new gear of mental toughness. "The goal was to make it through BUD/S," says a former friend who knew about the training. "It had nothing to do with golf."

To many people inside Tiger's circle, Jack Nicklaus' record of 18 majors wasn't as important to Tiger as it was to the golfing media and fans. He never mentioned it. Multiple people who've spent significant amounts of time with him say that. When Tiger did talk about it, someone else usually brought it up and he merely responded. The record instead became something to break so he could chase something that truly mattered. He loved the anonymity of wearing a uniform and being part of a team. "It was very, very serious," the friend says. "If he had had a hot two years and broken the record, he would have hung up his clubs and enlisted. No doubt."

Tiger talked about some of these military trips with his friends, including describing skydiving to Michael Jordan, who saw a pattern repeating from his own past. Years before, he'd lost his father, and in his grief, he sought solace doing something his dad loved, quitting the Bulls and riding minor league buses for the Birmingham Barons. "It could be his way of playing baseball," Jordan would say years later. "Soothing his father's interest."

Jordan looked sad as he said this, perhaps feeling the heaviness of it all or even the luck involved. He somehow got through his grief and reclaimed his greatness, while Tiger has tried and failed over and over again.

"Ah, boy," Jordan sighed.

“If he had broken Nicklaus’ record, Tiger would have hung up his clubs and enlisted. No doubt.”

- A FRIEND OF TIGER'S

THE POINT OF no return came on July 31, 2007, a date that means nothing to the millions of fans who follow Tiger Woods but was the last real shot he had to avoid the coming storm. From the outside, he was closing in, inevitably, on Nicklaus. But inside his world, a year after his dad died, things were falling apart.

On June 18, Tiger became a father. In July, he flew a porn star to Washington, D.C., according to a tabloid, to meet him during his tournament, the AT&T National. He'd already met many of the mistresses who would come forward two years later. According to The Wall Street Journal, the summer of 2007 is when the National Enquirer contacted his camp to say it had caught him in an affair with a Perkins waitress. Negotiations allegedly began that would kill the tabloid story if Tiger agreed to sit for an interview and cover shoot with Men's Fitness, owned by the same parent company as the Enquirer. He did. The magazine hit newsstands on June 29.

On July 22, he finished tied for 12th at the Open Championship, and then came home. In the weeks afterward, he'd announce that he'd ruptured his left ACL while jogging in Isleworth. His news release did not mention whether he'd been running in sneakers or combat boots. At the time, he chose to skip surgery and keep playing. Tiger's account might be true, as might the scenario laid out in Haney's book: that he tore the ACL in the Kill House with SEALs. Most likely, they're both right. The knee suffered repeated stresses and injuries, from military drills and elite-level sports training and high-weight, low-rep lifting. A man who saw him doing CQD training says, "It's kind of funny, when you have an injury it almost seems like a magnet for trauma. He almost never had something hit his right knee. It was always his left knee that got kicked, or hit, or shot, or landed on. Always the left knee."

Whatever happened, he didn't take a break. Two days before the tournament in Akron, he was in Ohio. That night, July 31, his agent, Mark Steinberg, had people over to his home near Cleveland, including Tiger. According to both Haney's and Williams' books, Steinberg said the time had come for an intervention over Tiger's military adventures. While Steinberg has a reputation as a bully in the golf world, he cares a great deal about his client and friend. This all must have seemed insane to someone who just wanted to manage a great athlete: secret trips to military facilities, running around a golf course in combat boots, shooting guns, taking punches.

That night after dinner, Steinberg took Tiger into his downstairs office, a room in his finished basement. What they talked about remains private. But this was the moment when Tiger could have connected the dots and seen how out of control things had become. Everyone felt good about the talk. Afterward, Haney wrote, Tiger was different and the military trips became less of a distraction.

That's what they thought.

Consider Tiger Woods once more, tabloids snapping grainy long-distance photos, his marriage suddenly in danger and with it the normalcy he lacked everywhere else, his body taking a terrible beating from SEAL training and aggressive weightlifting, a year after losing his father, adrift and yet still dominating all the other golfers in the world. They never were his greatest opponent, which was and always will be a combination of himself and all those expectations he never could control. Tiger won Akron, then won his 13th career major the following week at the PGA Championship in Tulsa, and then, 15 hours after getting home from the tournament, he packed up and flew off again to do CQD training with Dieter. Steinberg's warning was just 13 days old.

EVERYTHING ELSE MIGHT as well have been chiseled in stone on the day he was born. The two knee surgeries in Park City, Utah, a year later. The three back surgeries. The Thanksgiving night he took an Ambien and forgot to erase his text messages, and how that enormous storm started small, with Elin calling numbers in his phone, confronting the people on the other end, including Uchitel's friend Tim Bitici, who was in Vermont with his family when his phone rang. The horrors big and small that followed. The butcher paper taped up over the windows to block the paparazzi. The sheet his crew hung over the name of his yacht. The internet comments he read while driving to Augusta National before the 2010 Masters, obsessed over what people thought. The questions from his kids about why Mommy and Daddy don't live together, and the things he won't be able to protect them from when their classmates discover the internet. The tournament where he shot a 42 on the front nine and withdrew, blaming knee and Achilles injuries.

That day, Steve Williams saw a friend in the parking lot.

"What happened?" his friend asked, incredulous.

"I think he's got the yips, mate," Williams replied.

In the 1,303 days between his father's death and the fire hydrant, Tiger set in motion all those things, and when he can finally go back and make a full accounting of his life, he'll realize that winning the 2008 U.S. Open a year before the scandal, with a broken leg and torn ACL, was the closest he ever got to BUD/S. He could barely walk and he still beat everyone in the world. He won and has never been the same. The loneliness and pain tore apart his family, and the injuries destroyed his chance to beat Nicklaus and to leave fame behind and join the Navy. He lost his dad, and then his focus, and then his way, and everything else came falling down too.

But first, he got one final major.

"I'm winning this tournament," he told his team.

"Is it really worth it, Tiger?" Steve Williams asked.

"F-- you," Tiger said.

No comments:

Post a Comment